💡 How Ewake reduced SRE operational toil for Booksy: read the article!

All articles

Product

·

Feb 3, 2026

·

7

min read

AI agents are hot at the moment. I first heard the word “agentic” less than three years ago, and today it feels like I can’t escape it. It feels like the actual meaning of the term is getting lost in the hype noise. Is an agent a digital employee? Is it some kind of machine spirit that inhabits my over-engineered AI toaster?

This article is an attempt to cut through the hype and noise, and to give a human-readable, grounded perspective on what an AI agent actually is, from a traditional software engineer’s perspective.

A little note about me: I come from a very traditional software engineering background. Before I joined Ewake as a founding engineer, I spent nearly 8 years working for a tech giant with a bridge for its logo, mainly on an embedded C++ app for videoconferencing endpoints. I’m as cynical about the AI hype machine as anyone, but rather than dismissing it outright or becoming a dyed-in-the-wool vibe coder, I’ve developed a feeling for where this new thing fits.

Another Software Revolution(?)

Last summer I watched Andrej Karpathy’s talk Software 3.0: Software in the Age of AI, and I found it persuasive. In it, he proposed three generations of software:

Software 1.0: Traditional Software (Written by humans, explicit logic).

Software 2.0: Machine Learning (ML models with learned weights).

Software 3.0: Prompts (Natural language instructions compiled by an LLM).

In his Software 2.0 essay, Karpathy observed that Software 2.0 was “eating” Software 1.0 at Tesla. The parts of the system’s functionality that were the result of human-written logic were being replaced with models and weights.

For brevity, I’ll call traditional software Type 1 and LLMs Type 3.

He extends this argument, predicting that Type 3 “software as prompts” will do a similar job, gradually taking over more and more of the functionality of the codebase, without fully eliminating the other two.

The important thing to takeaway here is that Type 1 Code didn’t go away — the proportions just changed. This is the case with AI agents. An Agent is simply a robust chunk of Type 1 code wrapping a piece of Type 3 code.

For the sake of this article I’ll anthropomorphise the agent, but in reality, it’s just probabilistic code that we have to manage with traditional engineering.

The Brain

1. The Loop

The core of an AI agent is a loop. The term that the industry is settling on is “ReAct” agent (Reflect and Act). The agent reflects on its situation, then takes an action, then reflects on the result of that action, then takes another action, etc.

Fundamentally, this is a REPL (Read-Eval-Print Loop) — a familiar sight to any software engineer. The difference here is that there’s a chunk of probabilistic code involved that makes the decisions, but the concept stands.

As AI engineers we have the option of rolling our own agent loop using primitives like LangGraph or Vercel’s AI SDK. However, in the last year and change we’ve seen the rise of more opinionated frameworks, from high-level abstractions like Crew AI, to code-centric tools like Pydantic AI and Mastra (our current weapon of choice). This ecosystem is still young but it’s maturing rapidly.

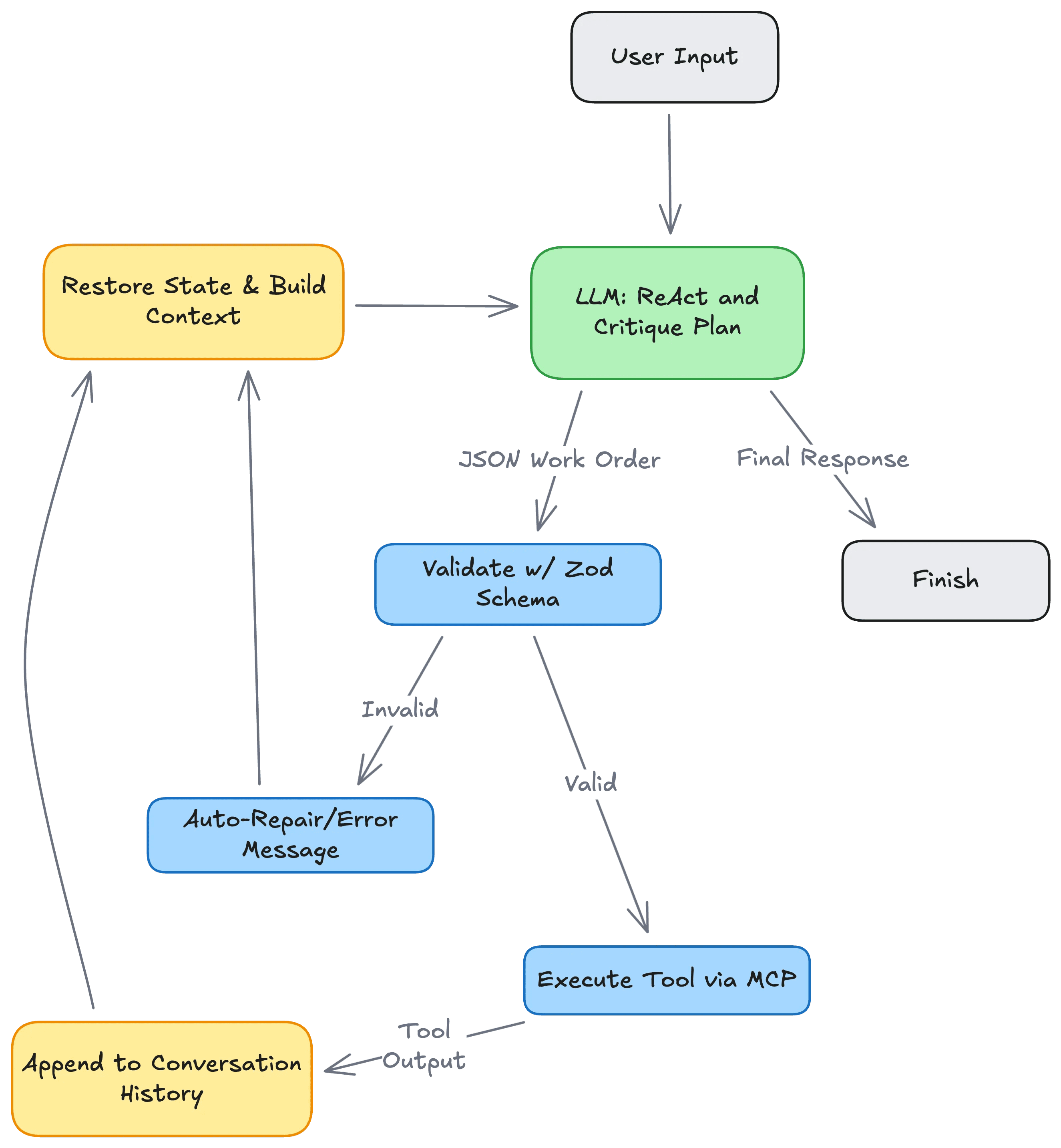

Here is what that loop actually looks like in practice. You can see how the probabilistic “Brain” is completely surrounded by deterministic Type 1 processes.

2. The Internal Dialogue

You might hear the analogy that an Agent is “two LLMs talking to each other.” That sounds like the end of Her (2013), but in reality, it’s just a software pattern called Actor-Critic.

Why do we do this? Because LLMs are prone to hallucinations. They are confident liars. However, research shows that LLMs are significantly better at critiquing logic than generating it.

So, we treat the Agent like a development team:

Call 1 (The Actor): The “Junior Dev.” It writes the code or generates the plan.

Call 2 (The Critic): The “Senior Dev.” It reviews the plan, checks for bugs, and rejects it if it looks wrong.

It’s not a split personality; it’s just running a code review in natural language before we let the code run in production.

3. The Memory

Here is the headache: LLMs have no memory. They are stateless.

To create a coherent conversation, we have to perform a massive “State Restoration” on every single turn. We have to re-inject the user’s prompt, the previous replies, the tool outputs, and the system instructions every time we loop.

It’s an inventory management problem. We are effectively re-installing the Operating System for every single iteration. And since we pay by the token, this gets expensive fast.

“Context Engineering” isn’t magic; it’s just ruthless compression to ensure we don’t go broke while debugging a single alert. Honestly, this is where 80% of the actual engineering work in building agents lives right now — figuring out exactly what data to show the model at any given moment to get the best result.

The Hands

Right now, we have a brain in a jar. It can reason, but it has no hands. It can’t fetch your Datadog logs and it can’t open a pull request. It is trapped in the text box.

To fix this, we give the Agent Tools. Think of these like API wrappers for the illiterate. We create a registry of functions (Type 1 code) and describe them to the LLM.

When the Agent wants to check an incident, it doesn’t run the command. It writes a “Work Order” in JSON.

JSON

Agent: { "tool": "get_logs", "service": "checkout", "level": "error" }

Runtime: “I see you want logs. I will execute that safely and paste the result back to you.”

This is where MCP (Model Context Protocol) comes in. Think of it as USB-C for AI. Instead of writing custom drivers for every single tool, MCP provides a standard plug. It allows our probabilistic Type 3 code to talk to our rigid Type 1 infrastructure without breaking things.

The Handshake

There is a conflict at the interface between our deterministic logic and the probabilistic LLM. How do we make them play nicely together?

The answer, as is so often the case, is defensive programming and schema validation.

We don’t trust the agent. We force its output into a strict structure. If the LLM outputs a string where we expect to have an int, the Type 1 code catches it and either forces a retry or throws an error.

This is all handled quite natively by the agent frameworks I mentioned earlier, using well-known utilities like Zod for schema enforcement.

To Wrap Up

People are excited about the potential of Agents, and rightly so. But we need to stop treating them like magic and start treating them like what they are: a new type of application architecture.

At Ewake, we bet on this architecture because production environments present the ultimate Type 3 problem. No two incidents are the same. You cannot write a static if/else block for "the database is slow because a noisy neighbour is hogging CPU." That requires reasoning.

But we also can’t let an LLM hallucinate a DROP TABLE command. That requires the safety of Type 1 code.

Agents allow us to bridge the gap. We use the LLM to understand the messy, chaotic reality of an outage, and we use traditional software engineering to ensure the response is safe, valid, and deterministic.

So, yes, the hype bubble will burst. The AI Toasters will vanish. But this pattern (probabilistic reasoning inside a deterministic cage) is part of the future of how we build software. It’s still code. It’s just a new pattern.